When Angel Di Maria's Juventus move was first mooted in June, Gigi Buffon argued that the Argentine's arrival would not only be a massive boost for the Bianconeri, but also Italian football. "For Serie A," the goalkeeping icon told Gazzetta dello Sport, "Di Maria is like [signing] Maradona."

It was meant as a massive compliment to the enduring excellence of a player that Buffon has long admired.

In reality, though, it was a shocking illustration of how far Serie A has fallen since the golden age of Maradona, Marco van Basten and Lothar Matthäus. An Italian team hasn't won the Champions League since 2010, while the Azzurri have failed to qualify for a second consecutive World Cup, making the Euro 2020 triumph look like a glorious anomaly.

As AC Milan president Paolo Scaroni told Il Foglio, "In the last 20 years, nearly everyone has overtaken us... Serie A has become the Serie B of Europe."

Even the league's most avid followers would find it difficult to disagree, so frustrated have they become by the reckless way in which the Italian game is run.

After an era of financial turmoil caused by the club's previous Chinese owners, Milan claimed their first Scudetto in 11 years last season, the result of a prudent approach imposed upon the club by Elliott Management, yet Italy's reigning champions have had trouble landing their top transfer targets this summer.

Sven Botman looked set to join from Lille but moved to Newcastle instead, while Renato Sanches ended up at Paris Saint-Germain – neatly highlighting the twin threat posed to the standard of Serie A right now by the Premier League and state-backed super-clubs.

Even when Milan belatedly managed to strengthen their squad with the acquisition of Charles De Ketelaere from Club Brugge, former Netherlands international Jan Mulder offered a withering review of the 21-year-old's San Siro switch.

"I don’t understand anything about this transfer," the European Cup winner told HLN. "Obviously, he should have gone to the Premier League because it’s the best league in the world.

"Milan and Serie A – that's where celebrities go in their twilight these days."

Serie A undeniably has a major image problem, which is why the Premier League is making approximately 10 times as much money from the sale of international TV rights.

Last season's title race was utterly compelling, one of the most competitive and exciting in Europe, and yet the perception remains that Italian football is a grossly inferior product to what's on offer in England.

However, Serie A only has itself to blame in this regard. It's not only failing miserably to market its product to the world; it's long been an active participant in its slow and sad decline.

La Liga president Javier Tebas asked last year, "How is it possible that Italian football is making less money than Spanish, when it has a bigger population with a higher income per capita?"

The answer is gross mismanagement at every level of the game over a sustained period of time.

A number of the major players in Italian football, including Juventus president Andrea Agnelli, have blamed the Covid-19 crisis. However, the pandemic didn't create football's fragile economic framework; it just knocked it over.

"Serie A has suffered, and is still suffering, more than the other top European leagues because even before Covid, it was in poor health," Marco Iaria of the Gazzetta dello Sport told GOAL.

"There was a lengthy crisis of competitiveness in relation to international competition, caused by management errors and the lack of a clear, long-term strategy.

"In this era of TV rights, all of the money that went into the Italian clubs' coffers was consumed by sporting costs, wages and transfers, without making the necessary investment in infrastructure, promotion, marketing, and the simple know-how required for Serie A clubs remaining attached to the first-class carriage of the train.

"The arrival of the nouveau riche, who have directed their money elsewhere, and the decline of the old Italian patron, resulting in the historic sales of Inter and Milan by Massimo Moratti and Silvio Berlusconi, respectively, took care of the rest.

"For example, in 2018-19, the last full season before the Covid-19 crisis, Serie A lost nearly €300 million (£260m/$350m) despite €700m (£600m/$820m) of capital gains, and had accumulated €2.5 billion (£2.1m/$2.9m) of net debt.

"So, that was the troubling nature of the pre-pandemic scene."

Getty/GOAL

Getty/GOALThe league's subsequent struggles were, therefore, inevitable.

Milan, luckily, had already embraced a more frugal financial plan before Covid-19 first suspended play, and then forced games to be played behind closed doors.

Juventus, though, required a historic injection of capital from parent company EXOR in order to continue signing players like Dusan Vlahovic, while Inter have had to sell top players and drastically reduce their wage bill just to remain afloat.

Indeed, the summer of 2021 was brutal for not only the Nerazzurri, but also Serie A in general.

In one window, the league lost its newly crowned MVP (Romelu Lukaku, to Chelsea), its best goalkeeper (Gigi Donnarumma, to PSG), centre-back (Cristian Romero, to Tottenham), right-back (Achraf Hakimi, to PSG) and its most high-profile player (Cristiano Ronaldo, to Manchester United).

This summer has arguably been worse, though. Lukaku may have returned, along with Paul Pogba, who has re-joined Juve, but Kalidou Koulibaly and Matthijs de Ligt have both left, for Chelsea and Bayern Munich respectively.

Koulibaly was a legend in Naples, while De Ligt was meant to be the leader of the next great Bianconeri backline. Instead, he has departed, taking one shot after another at the style of play and intensity of training in Turin.

This isn't just about high-profile players, though. What's made this summer particularly painful, though, is the realisation that Serie A can no longer retain its mid-level talent and exciting up-and-comers – let alone its established stars.

Gianluca Scamacca, for example, has long been linked with the likes of Inter and Juventus. In years gone by, a transfer to either would have been the obvious and inevitable progression for a young Italy international.

Instead, Scamacca signed for West Ham United, the seventh-best team in England, and he will be joined in the Premier League next season by Udinese's exciting Italy Under-21 international Destiny Udogie, who will move to Tottenham next summer.

It's also not a particularly good look for the league that Euro 2020 winners Lorenzo Insigne and Federico Bernardeschi have left for MLS, Inter couldn't convince Ivan Perisic to ignore Tottenham's overtures, Lucas Torreira has swapped Fiorentina for Galatasaray, and Arthur Teate and Aaron Hickey joined Rennes and Brentford after breakout seasons at Bologna.

Again, it's all a question of money, and the way in which Serie A has squandered its past position of dominance.

"What has changed compared to 20 years ago, when Italy had three teams in the top five of Deloitte's Football Money League?" former AC Milan vice-president and current Monza CEO Adriano Galliani asked in a recent interview with Calcio e Finanza. "We didn't build stadiums.

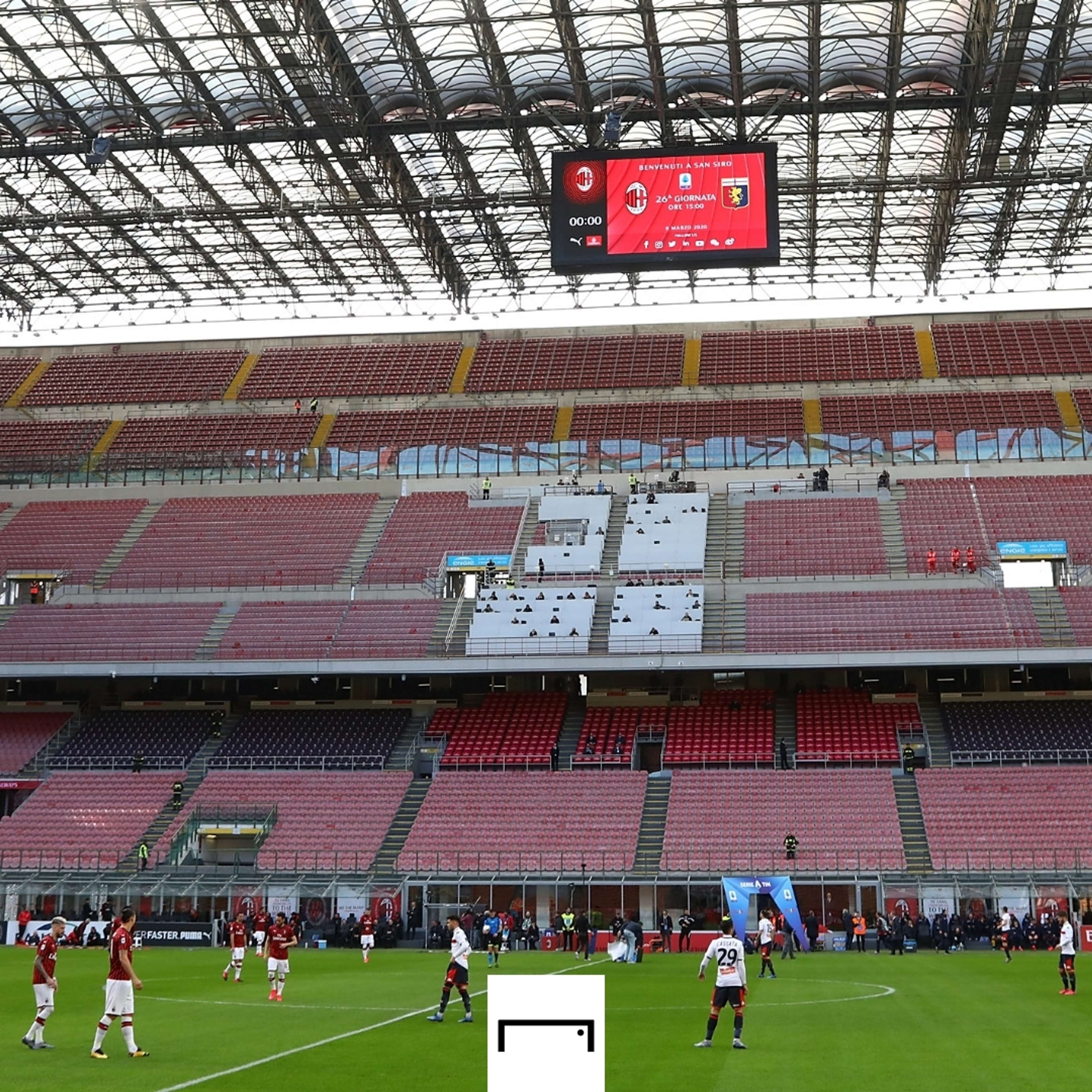

"We have the ugliest stadiums in Europe and this affects revenues and TV rights, because an ugly and empty stadium is not sold on TV.

"And we did not build the stadiums because bureaucracy held everyone back, because the authorities, for a long time, were asking for the construction of the athletics track and because there are always a thousand obstacles, like at San Siro, for example."

Indeed, a new law introduced in 2013 was meant to make the redevelopment or construction of stadia easier. However, nearly a decade on, Serie A remains bogged down in bureaucracy, resulting in plans for new stadia either being delayed for an eternity.

"And while we wait, the world goes forward," Scaroni told Calcio e Finanza. "Since 2013, there have been three new stadia built in London alone."

The net result is that ambitious owners end up disillusioned, feeling as if they're banging their heads against a brick wall, wondering if there's any point in even signing world-class players if they can't provide them with a suitably grand stage on which to perform.

"We can take the best opera singers in the world," Scaroni said, "but if we then make them sing in a shed instead of at La Scala... it's a big difference."

Italian football, then, is dealing with a number of self-inflicted wounds and the question now is how it can possibly recover?

Galliani is among those that believe the European Super League is the answer, albeit without English clubs, who are reaping the rewards of creating their own Super League in 1992. "There should be a Brexit in football too," he controversially suggested.

And, despite the humiliating collapse of the ESL after a fan backlash in England, Agnelli hasn't given up on realising the dream he shares with Real Madrid president Florentino Perez. They are still fighting court battles to see the breakaway competition come to fruition.

For some football fans, the idea is now more palatable because of the organisers' willingness to abandon the original concept of a 'closed' league.

Several supporters have also begun highlighting stories about the Premier League's financial might and sarcastically adding 'But the Super League was the problem...'

It's certainly not the solution, though, at least not for the game as a whole.

The Premier League's wealth is undeniably a major cause for concern, given the effect it is having both on the transfer market and competitive balance in continental competition.

However, as Gianluigi Longari of Sportitalia TV told GOAL, the ESL isn't "a magic wand" capable of solving all of Italy's problems.

Getty/GOAL

Getty/GOAL"Granted, we do seem to be in a worse position without the Super League, which would have at least seen 12 clubs on more or less the same financial footing with the same chances of success," Longari acknowledged.

"Now, we arguably only have three or four in all of Europe, so it's clear that drastic changes to the system are required.

"You only have to think of the fact that the team that wins the league in Italy earns more or less the same amount of money from TV rights as a team just promoted to the Premier League from the Championship.

"So, the situation in Italy is grave, and much worse than in other countries, because the money from TV deals is not sufficient.

"But there is no magic wand that can make all of these economic issues go away. The only possibility for the clubs is to avoid overextending themselves by trying to do things that they cannot afford."

And that is the cold hard truth. Italian clubs need to be less like Manchester United and Barcelona by wasting millions in the transfer market and more like Atalanta, and more recently Milan, by trying to live within their means.

The Super League would have represented nothing more than a quick fix for Italy's elite; it would have devastated the rest of Serie A, turning it into a veritable Serie B, making its smaller provincial clubs little more than prisoners of the kind of 'trickle-down' economics championed not so long ago by Donald Trump.

If there is to be any chance of reform, there first needs to be an acceptance of some short-term pain for long-term gain.

The entire structure of the game needs to be torn down and rebuilt, just like many of Serie A's crumbling stadia.

"The resources in football are becoming more and more concentrated at the top of the pyramid," coach Luca Gotti told GOAL.

"Before, there was a movement of money between Serie A, Serie B and Serie C. However, then we saw a big gap develop between Serie B and Serie A.

Getty/GOAL

Getty/GOAL"Television deals ended up putting more money in the hands of fewer clubs. So now, even within Serie A, the elite are almost completely detached from the rest.

"So, this is a long-running trend in football. The Super League was just the latest step in this direction.

"I think that there's a need for the management of La Lega and all of our club presidents to agree on a long-term plan.

"What's required is a vision for the future, covering the next five to eight years, which would allow us to bridge the economic gap to the richest clubs.

"The Premier League has reached an economic level with which Serie A presently can't compete.

"We're lacking a certain standard of excellence and this is often the result of our myopia. We don't see beyond our noses."

Such a damaging lack of foresight should no longer be tolerated.

The problem, though, remains a lack of unity among the game's stakeholders. There are still too many conflicting interests.

The Italian game remains plagued by parochialism and petty squabbles, which explains why Serie A failed to make the most of Cristiano Ronaldo's three-year stint at Juve, resulting in the value of its international TV deals falling rather than rising.

"I don't want to be pessimistic," Longari said, "But I don't see any solutions on the horizon."

Indeed, Di Maria is no Maradona. And even if he were, it would still take a lot more than one generational talent to save Italian football from itself.