On the day that Neymar became Brazil's all-time record goalscorer in a World Cup quarter-final loss to Croatia, Pele paid tribute to his successor with his characteristic humility. "Unfortunately, the day is not the happiest for us," he wrote from his hospital bed, "but you will always be the source of inspiration that many aspire to become."

He may as well have been talking about himself.

Pele was laid to rest in Santos on Tuesday, but if the moving scenes across both Brazil and the world illustrate anything, it is that he is, as the No.10 jerseys hanging outside Vila Belmiro stadium read, the 'Eternal King'.

FIFA president Gianni Infantino called on every country to name a stadium after Brazil's iconic No.10, so that he will be forever known to future generations. It's really not necessary, though. As Jose Mourinho once said, "Pele is football". The two are indivisible.

There is a reason why athletes of all ages from all over the world are presently paying tribute to him. It is because he transcended the sport as the game's first truly global superstar.

Next Match

Even the artist Andy Warhol felt compelled to admit, "Pele was one of the few who contradicted my theory: Instead of 15 minutes of fame, he will have 15 centuries."

Death, then, does not signal the end of Pele's legacy. On the contrary, in troubling, disillusioning times for 'The Beautiful Game', his passing has reminded us all of why we fell in love with both the game, and indeed Pele, in the first place.

Pele didn't just do everything first. He also did things that nobody has managed since, things that didn't seem possible for a mere mortal.

Indeed, even among the game's greats, Pele stood out, because he didn't appear to be of this world. As Michel Platini put it, "To play like Pele, is to play like God."

For that very reason, Ferenc Puskas always insisted that Alfred Di Stefano was the best player in history – because he felt Pele was more than a footballer. "He was above that," the legendary left-footer argued. Pele was, as Johann Cruyff argued, capable of surpassing "the boundaries of logic".

For example, Pele was not a tall man – yet he was an astounding header of the ball, as he proved in the 1970 World Cup final. "I told myself before the game that he's made of skin and bone like everyone else," Italy's Tarcisio Burgnich would later reveal. "But I was wrong."

Indeed, just 18 minutes into the game, Pele leapt high above Burgnich to power home a header from Rivellino's hooked cross.

Happily, the Italian No.2 wasn't too harsh on himself for being beaten so easily in the air. "I arrived hoping to stop a great man," he explained, "but I went away convinced I had been undone by someone who was not born on the same planet as the rest of us."

Burgnich wasn't alone in that regard. Just Fontaine scored 13 goals at the 1958 World Cup – and yet when he shared a pitch with Pele in the semi-final, he felt inadequate, as if he should give up playing football.

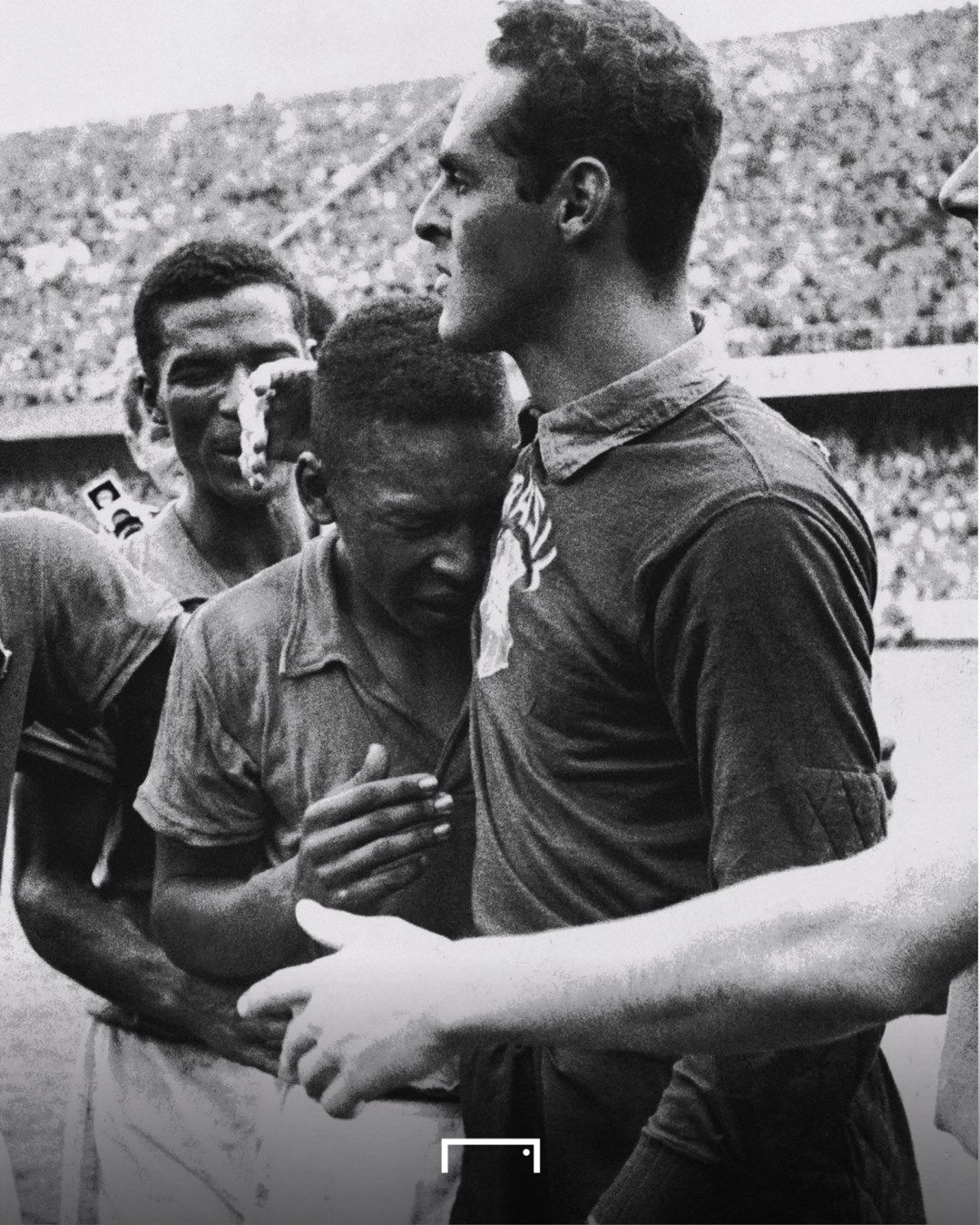

When Pele scored his stunning solo goal in the final, meanwhile, Swedish player Sigvard Parling admitted that he considered applauding. Pele was just 17 at the time.

.jpg?format=pjpg&auto=webp&width=3840&quality=60) Getty

GettyHe would go on to win two more World Cups, with his masterpiece arriving in 1970 when he played the role of the conductor in a Selecao symphony that enchanted football fans like no other team before, or since.

It is, therefore, curious that in recent times a misguided belief has taken hold that Pele's greatness is an illusion, and his staggering numbers and trophy tally misleading.

The principal argument appears to be that he never proved himself in Europe, which is bizarre given he scored freely against the continent's top teams for both Santos and Brazil, and in an era in which forwards were offered next-to-no protection by referees. One only has to look at the way in which Pele's Brazil were literally kicked out of the 1966 World Cup to find evidence of the brutality of the game at the time.

It's also worth remembering that Pele was deemed a national treasure, thus preventing him from moving overseas during his peak years. That shouldn't diminish his domestic dominance, though. Brazil, after all, boasted many of the game's top talents, as underlined by the Selecao winning three of the four World Cups between 1958 and 1970.

Ultimately, though, the petty squabble over the title of the game's greatest player is irrelevant. What matters, as Pele said himself, is the inspiration, the memories, the legacy he has left behind.

Shortly before he passed, Pele wrote that "Football is joy. It's a dance. It's a real party." So, while this day is most definitely "not the happiest day for us", it should also be a celebration of a remarkable life, a fantastic footballer and an eternal king.

Maybe Burgnich and Platini were right all along. Maybe Pele was never of this planet. Maybe he was sent from above. And maybe now he has simply gone home.