A couple of years before Italy failed to qualify for the first of two consecutive World Cups, Gheorge Hagi issued a warning.

"You have to be careful," he told the Gazzetta dello Sport in 2015. "You have to be able to develop No.10s because, right now, Italy doesn't have a true No.10, and this is a real problem for the Azzurri."

The lack of a goalscorer has arguably proven an even bigger issue in the intervening years but there's no denying that true No.10s are a dying breed in Italy.

But it's not like they're flourishing elsewhere either. Truth be told, there isn't much room for No.10s anymore... Well, not No.10s like Hagi: attacking midfielders allowed to focus solely on creating and scoring goals.

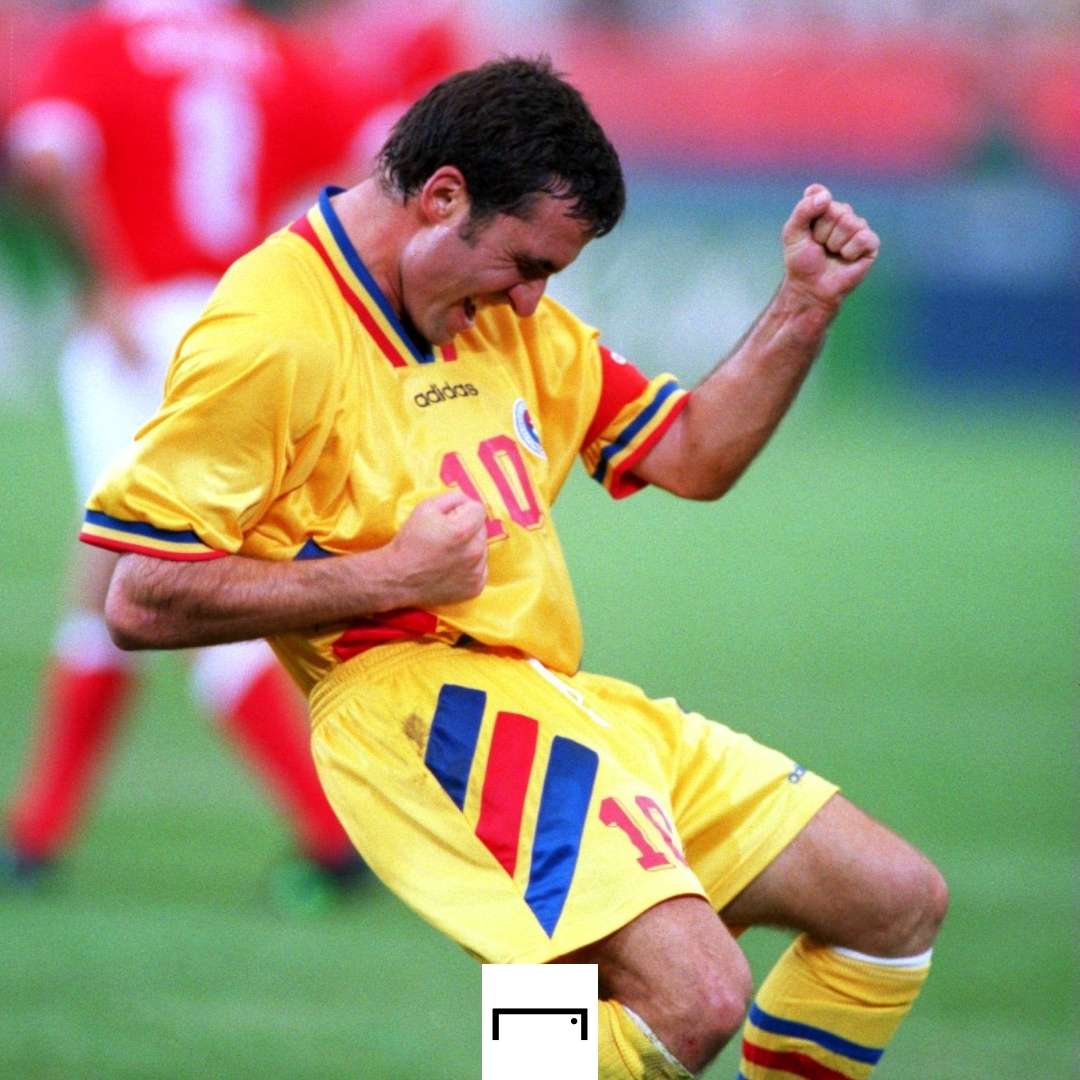

The Romanian was the personification of the old-school trequartista: lazy, temperamental and inconsistent – but capable of moments of pure genius.

Which helps explain why he only became a global star at the age of 29.

Hagi's natural ability had been obvious from a young age. He was playing in competitions with professionals at the age of 11 and would become a key player in the Steaua Bucharest side beaten by the mighty AC Milan in the 1989 European Cup final.

Rossoneri coach Arrigo Sacchi even tried to sign him for the following campaign but Hagi instead joined Real Madrid after Italia 90.

Getty/GOAL

Getty/GOALRamon Mendoza had been the determining factor in Hagi's decision, even flying to Romania to make the deal happen, and the Blancos president also did everything to help him settle in Spain.

Hagi, though, struggled in the spotlight of the Santiago Bernabeu, awestruck by the likes of Hugo Sanchez.

"I failed," he would later admit. "Faced with all those superstars, I nearly sh*t my pants."

He lasted just two seasons in La Liga before being surprisingly sold to Brescia.

Despite the 'Romanian revolution' being overseen at the provincial outfit by Mircea Lucescu, Hagi again flattered to deceive, this time in a side that was relegated at the end of his first season in Italy.

By that stage, he appeared doomed to be remembered as one of the game's great unfulfilled talents.

Hagi, though, flourished in Serie B and arrived at the 1994 World Cup with renewed confidence, which he showed off just 35 minutes into Romania's opening game, against Colombia.

Picking up possession wide on the left-hand side of the field at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena, and with Florin Raducioiu moving menacingly towards the penalty area, Hagi looked certain to try to pick out the striker.

As the ball nestled in the back of the net, Hagi did a little jig on the sideline while everyone else asked themselves: Did he really mean to score from there? But he did.

Hagi had studied Colombia beforehand. He had noticed that Cordoba had a tendency to drift off his line. And had already had a couple of 'sighters' before eventually succeeding at the third attempt.

There was also the fact that Hagi had long been bamboozling goalkeepers with one of the most gifted left boots the game has ever seen. He hadn't become known as the Maradona of the Carpathians for nothing, after all.

For a long time, that nickname felt like hyperbole. But for one glorious summer, Hagi looked like Maradona's match.

The great shame, of course, is that they didn't get to square off in the last 16.

Getty/GOAL

Getty/GOALRomania against Argentina proved one of the great games in World Cup history, but Maradona had already been sent home from the United States in disgrace after failing a drugs test.

He was forced to watch the game on TV and argued that the game had been decided on the field, rather than on it.

On that particular day, though, one wonders if a 33-year-old Maradona would really have been capable of upstaging Hagi, who teed up Ilie Dumitrescu for Romania's second goal with the most wonderfully of weighted of passes, before then sealing a famous 3-1 win with a fine right-footed strike in the second half.

Romania coach Anghel Iordanescu called Romania's victory "the greatest event celebrated by our people since the revolution", and Hagi was the leader of this particular rising.

At that stage of the tournament, when Hagi looked around at the seven other remaining sides, he "didn't see anyone better than us".

They were certainly the neutrals' favourites.

An attack-minded team that also featured Gheorge Popescu pulling the strings in midfield, and Dan Petrescu bombing forward from right-back didn't just play free-flowing football; there was also, crucially, a defensive vulnerability about them, which had been exposed in their 4-1 loss to Switzerland in the group stage.

When Romania played, excitement was virtually guaranteed and they were involved in another cracking contest in the quarter-finals, against Sweden, but were this time beaten on penalties, after being five minutes away from victory in extra time.

With all due respect to the Scandinavians, and quality players like Henrik Larsson and Tomas Brolin, their victory represented a great loss for the tournament, as the watching world had fallen in love with what Hagi later called the "fantasy style of our football".

Indeed, Romania were more Brazilian than the Brazilians themselves at USA '94.

The Selecao may have triumphed but did so playing a dour brand of football that did not sit easily with the purists back home.

It would have been fascinating, then, to have seen Romania and Brazil meet in the semi-finals, particularly as it would have also seen Hagi go head to head with Romario.

As he later lamented with characteristic humility, "I think we were so unlucky to lose when we did because, at that moment, I was the best player in the tournament. When we went out, I lost that position."

Getty/GOAL

Getty/GOALHis impact did not go unrecognised, though.

Hagi, who had been labelled "A Romanian version of Wayne Gretzky" by an adoring American public, was included in the team of the tournament, and then secured a return to La Liga, this time with Barcelona, going on to become one of the select few players to play and score for two of the game's great rivals.

Once again, he would endure great frustration in Spain, playing nowhere nearly as regularly as he would have liked.

But he learned lessons under the legendary Johan Cruyff that would serve him well both at the tail end of his playing days at Galatasaray – where he achieved legendary status during a remarkable renaissance – and then as a coach, club owner and academy founder in his native Romania.

His influence on his nation's football history, then, is unquantifiable. Back home, he is just known as 'The King'.

Hagi had his flaws, of course. Even Lucescu admitted that his compatriot had "trouble with consistency", but argued such "artists" had to be allowed to do whatever they wanted, simply because they were capable of doing whatever they wanted with a football.

Indeed, for footballing romantics, Hagi represents a certain freedom of expression that has been long since lost.

He is very much a player from a bygone era: for better and for worse, a "true No.10". And one of the last of his kind. We will truly never see his like again.