Over the last two years, understanding of mental health problems in the UK has changed dramatically.

Historically, if you were struggling with personal issues, you were ostracised. However, through very honest and frank introspective accounts by people in the public eye, having the strength to come forward and admit to struggling with forms of anxiety and depression, the narrative has shifted to the point where society as a whole is beginning to understand that these are issues that can and do happen to everyone. The key is managing mental wellbeing as you would diet or exercise.

Football has been a strong catalyst for change in men’s mental health discussions. Traditionally, the notion of being a strong man meant being stoic and composed; displaying any sign of emotion was seen as a weakness.

But things have changed thanks to the incredibly brave and honest accounts of mental health issues by players like Danny Rose, Dean Windass and Marvin Sordell. In truth, to mention just a few names does a disservice to the vast number of people who have come forward to bear their soul.

These personal stories of struggle have been vitally important to the future of our mental health management, as it changes the idea of mental wellbeing in people’s minds, but it also breaks down the biggest illusion depression creates – the notion that you are alone.

It was that aspect of the issue which led me to making the documentary 'One of a Number: Surviving football's ruthless system'.

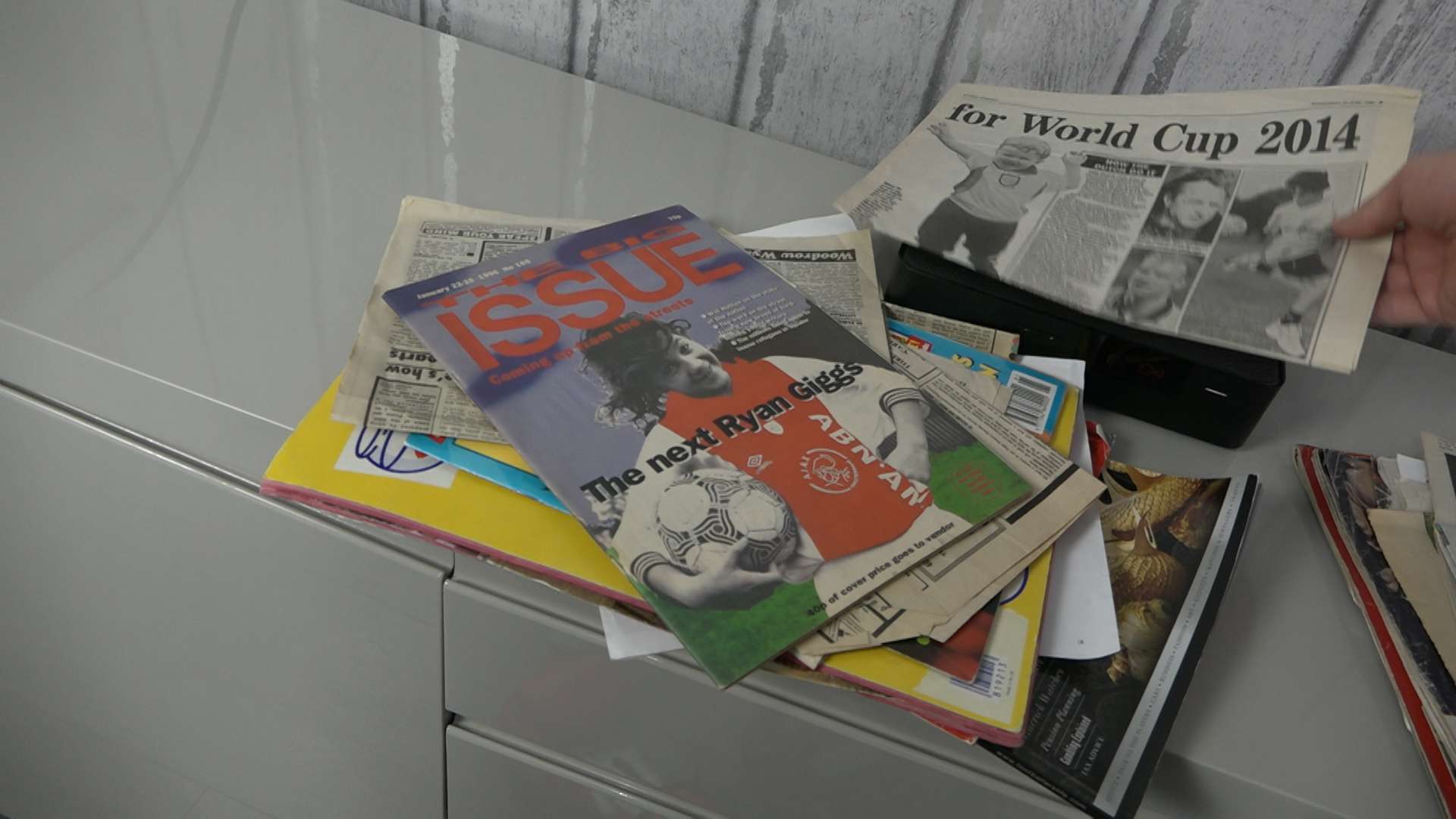

Since I joined Goal in November 2016, we have featured several pieces with players discussing their footballing journey and its impact on their personal lives: Sonny Pike, Pajtim Kasami, Ryan Smith, Kyle Ebecilio and many more.

Being in the room as producer/camera operator you have a slightly removed, almost bird's eye view of the situation and there were patterns, common key words and phrases that resonated with experiences I’d had in my previous job.

Before I became a journalist, I spent most of my 20s working in schools, including two and a half years at a primary school, where I was a teaching assistant for Year 4 and 6 classes. As part of my role, I was on playground duty every day and, given my love of football, was always in charge of the five-a-side cage.

At the time, there were several talented young players at the school, including one pupil who was at an academy.

I had never seen a child his age that talented. But he struggled with managing his emotions and would sometimes lash out at his team-mates, basically because they weren’t as good as him and his competitiveness spilled over in an emotional response.

When this happened, I would often have no choice but to send him off, which resulted in a more extreme emotional reaction. He would then isolate himself, either somewhere in the playground or his classroom.

I spent a lot of time thinking about how to manage these situations, as I feel it would have been very easy to dismiss his actions simply as ‘bad behaviour’. But understanding that his reactions weren’t coming from spite or a desire to scald his classmates, it was his extreme desire to win, coupled with the fact that, as a seven-year-old, he was still developing social skills and didn’t understand why his team-mates didn’t pass to him, or missed a chance to score.

As a result, after any of these episodes, I would seek him out later in the day to talk about why I had sent him off, explain that he hadn’t been ‘bad’, discuss how to manage those feelings of frustration and to encourage his classmates rather than criticise.

This initiative was backed up by one of the contributors to the documentary, Robert Kempson, a specialist senior child psychologist based near Cardiff. Kempson encountered the world of academy football first-hand when his son Theo was scouted by Cardiff City but struggled with the emotional pressure of comparing himself to other talented children in his team.

“Children see the world and in a very black and white way," Kempson explained. "If you're being good, ‘I'm brilliant, I'm the best I am, I'm a good kid, I'm doing well.' Then you get told off and it's ‘Oh, I'm terrible.'

"There are very young kids who tend to bounce between extremes from good and bad. And what we're trying to do over time is to try to fill in the gaps and be and be a bit more comfortable with the fact that we we're not all good or bad.”

Of course, a talented footballer's emotional wellbeing is no more important than that of his peers. It is simply that he is exposed to a unique set of circumstances that can have a direct impact on his mental state.

For me, the strongest correlation between my experiences on playground duty and those of the players who have spoken out about mental health, is that notion of isolation. For any player who joins the academy system, chances are they will have quickly been identified as better than the rest of the kids in their class at school.

In most cases, this has a knock-on effect on that child’s social standing. Also, as Balham FC coach Joshua Fitzgerald-Smith mentioned when I visited their Under-7s training session; "When I was younger, if you were a better player, you were more respected, whether it's in the class or outside playing football. You always got more love or respect because you're seen as someone good at sports or someone that was ‘the man'."

There is a fundamental irony in the fact that a talent not specifically related to social interaction can have a bearing on how people treat you. If you’re identified as gifted from an early age, your social interactions can be shaped by something largely beyond your control.

Then, when you factor in the success and status that comes with talent, it is only natural for that person to base their self-perception and identity on their footballing skill.

However, as QPR consultant sport psychologist Misia Gervis explained to me, this can be dangerous if that status is taken away, by injury or eventual rejection by a club.

"It has to be about valuing the person first," she said. "Football is just something you do. It isn’t who you are, because the problems come when you invest in your identity and you have one identity. And then that identity gets taken away from you because you’re released – that is when you walk yourself to the edge of the precipice and fall off.”

Setbacks in a player’s career will happen at all ages and continue until they eventually leave the game. How players and those present in their lives react to setbacks is key moving forward. Helping players to develop emotional resilience will better prepare them for the eventual inevitability that ‘the dream will end’.

There is no one solution or set formula for solving mental health issues in football, owing to the complexity of every individual’s personal experiences. The idea of sharing and talking is always mentioned as the basis for any answer and it can become a bit of a throwaway comment that perhaps loses its impact.

However, as I have found putting this documentary together, communication is vital. Not only does empathetic discussion shatter the notion that we are alone in dealing with the issues we face, it can also help us find the answers that we had inside us all along.

Sometimes, it just needs a friend or a colleague phrase their perspective in a certain way for all of the pieces in the puzzle to click into place.

Overall, I feel we have only begun to scratch the surface of a multi-faceted issue that needs in-depth introspective and personal discussion to become a key part of footballing culture if we are to improve our understanding of the pressures players face on a daily basis and how that impacts on their sense of identity and wellbeing.