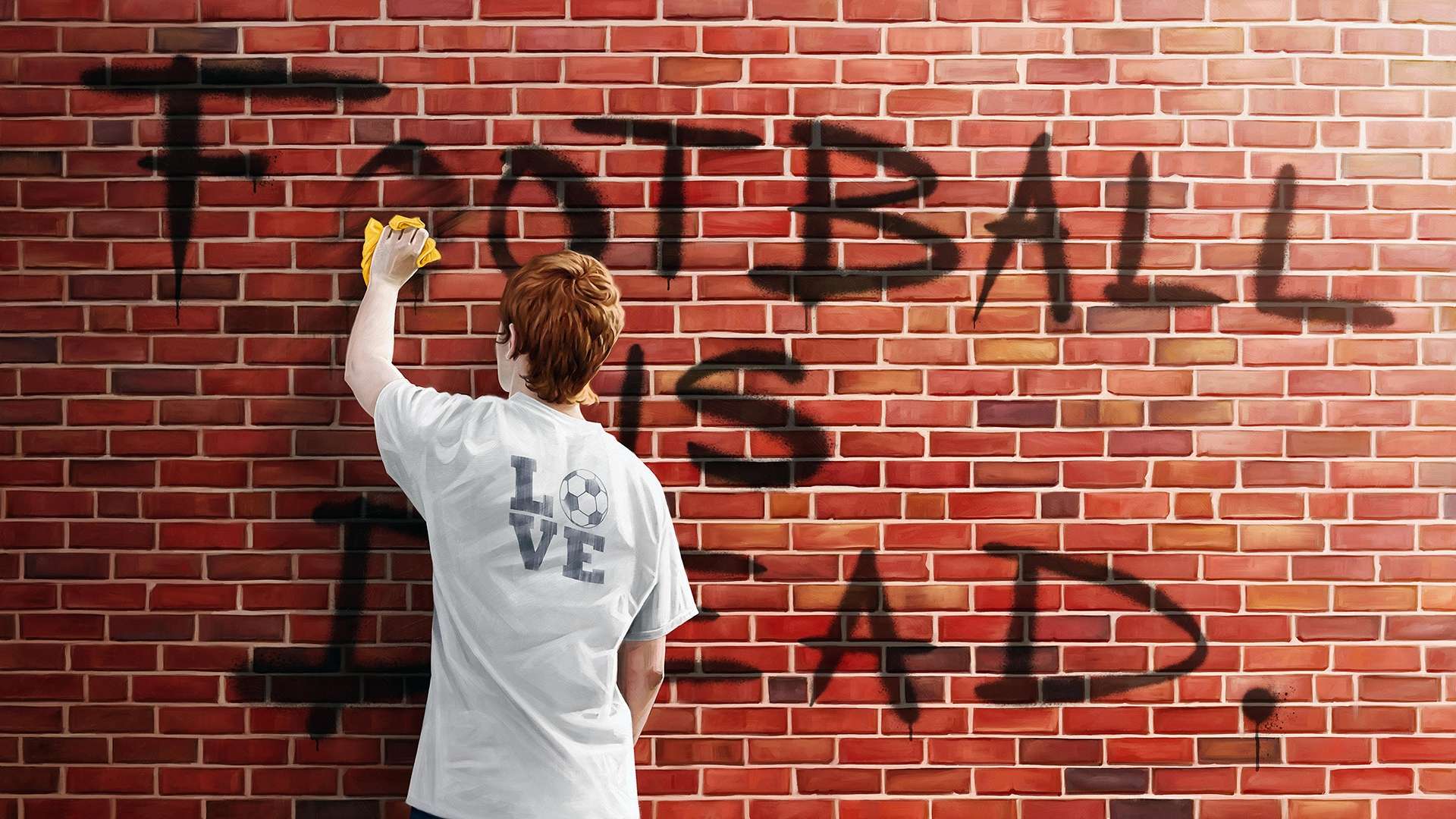

Jamie Carragher's reaction to the latest Super League proposal was succinct and heartfelt: "Oh f*ck off".

The former Liverpool stalwart was not the only member of the football family left both enraged and bewildered by the re-emergence of a controversial concept that just refuses to go away.

"I've been hearing about a Super League since I first started in football 10 years ago," Udinese's Magda Pozzo tells Goal, "and nothing has ever materialised.

"Every domestic league has its own history, tradition and its importance that makes it unique, so, I think a Super League would be very difficult to create."

Difficult, but not impossible, though. If history has taught us anything, it is that money is a powerful agent of change. Remember, the Champions League and Premier League have two things in common: both were born in 1992 and both were conceived by avaricious club owners.

The idea of a Super League first surfaced during that period of tremendous transformation – and returned several times since – but the threat feels different this time for a variety of reasons.

Firstly, there is the fact that the current agreement on the international match calendar will expire in 2024, meaning there is scope for restructuring the club game.

It is no coincidence, then, that the Super League speculation has returned now, with the game's major stakeholders already discussing Champions League reform.

"Any time the major clubs in Europe don't like the direction football is going in, the Super League is their go-to threat," says Josh Robinson, co-author of 'The Club: How the Premier League Became the Richest, Most Disruptive Business in Sport'. "It's a pretty handy tool for bending things in your favour.

"It's what we saw a few years ago in the Premier League when it came to international broadcasting rights. That was the first time we saw it as a threat that actually affected change because just as we were hearing talk of Real Madrid president Florentino Perez backing a Super League, the Premier League's 'Big Six' (Arsenal, Chelsea, Liverpool, Manchester City, Manchester United and Tottenham) were asking, 'Why are we sharing around the revenue from overseas TV deals when people are only tuning in to watch us?'

"So, that's when the Premier League tweaked the formula for the first time since 1992 and skewed it a little bit so that the 'Big Six' took a greater share of the foreign rights revenue.

"Nobody has forgotten that lesson, which is that the Super League isn't an idle threat; it can be an effective weapon. You can actually rattle league executives with it.”

Getty/Goal

The coronavirus outbreak has only exacerbated that sense of panic in boardrooms across Europe. As long-time Super League supporter Perez stated at Madrid's Annual General Assembly earlier this week, "Nothing will ever be the same again: the pandemic has changed everything. It has made us all more vulnerable, and football too."

Getty/Goal

The coronavirus outbreak has only exacerbated that sense of panic in boardrooms across Europe. As long-time Super League supporter Perez stated at Madrid's Annual General Assembly earlier this week, "Nothing will ever be the same again: the pandemic has changed everything. It has made us all more vulnerable, and football too."

The loss of revenue caused by having to play games behind closed doors has undeniably had a devastating effect on many club's finances. For example, the closure of Old Trafford is likely to cost Manchester United £100 million ($130m) in gate receipts alone, making their failure to reach the last 16 of the Champions League a major blow. And therein lies the appeal of a Super League for Europe's elite.

"I think it's a legitimate threat this time around because the pandemic has accelerated the need for certainty for many clubs," explains Kieran Maguire, author of 'The Price of Football'.

"Look at the massive losses posted by some huge clubs: Roma, Atletico Madrid, Barcelona, Borussia Dortmund. They are panicking now. They are worried that if this happens again, they could go under, so they’re looking to their Champions League because the money in football is in European competition.”

Indeed, it is worth noting that the last 16 of the 2019-20 Champions League, and the top 20 in this year's Deloitte Football Money League, were both comprised entirely of teams from Europe's 'Big Five' leagues: England, Spain, Italy, Germany and France. Champions League qualification, then, has become paramount to a club's prosperity, on and off the field.

The balance of power is already tipped in favour of the top teams through the unequal distribution of TV income and prize money within various domestic and European competition, and the incremental increase in Champions League places for the Premier League, La Liga, Serie A, the Bundesliga and Ligue 1.

However, sport by its very nature is unpredictable; football has, despite the disparity of wealth, retained its ability to produce shock results and surprising developments, such as lowly Atalanta making the Champions League last 16 for the second consecutive season while seven-time European Cup winners AC Milan haven't featured at all since 2014.

Consequently, the likes of Perez are aghast that dropping out of the Champions League is actually becoming slightly easier, and getting back in proving increasingly difficult. European Club Association (ECA) chairman Andrea Agnelli even publicly questioned whether provincial outfit Atalanta deserved to participate in last season's tournament on the back of "one great season" in Serie A.

Getty/Goal

Getty/GoalThe risk of missing out on Champions League qualification is certainly increasing in England. The Premier League's clubs may be buoyed by the most lucrative broadcasting deal in the world but that in itself has created problems for its 'Big Six', who are now under attack from ambitious mid-level rivals such as Everton, Leicester City, Wolves and Southampton.

"Until Leicester came along and won the title in 2016, there was little threat of the 'Big Six' being broken up," Robinson of the Wall Street Journal tells Goal. "They looked untouchable. There were always going to be European spots for them.

"But now that hierarchy is under threat. So, suddenly a struggling 'Big Six' club like Arsenal would have been better off in a Super League three years ago because they're not going to get back into the Champions League any time soon, and for a club of their ambition, it's crucial for them to have access to that well of money.

“It's very interesting, then, that we've reached a point where there are now more big teams in England than there are European spots, and there are no guarantees because of the competitiveness of the league.

"So, if the ‘Big Six’ were suddenly guaranteed entry to either a Super League or an expanded Champions League, I think they'd all wholeheartedly support it."

Indeed, there is mounting frustration among some owners of the Premier League's 'Big Six' about the distribution of wealth, which is why they recently tried to gain almost-total control of the English top flight via ‘Project Restart’. Essentially, in exchange for bailing out clubs further down the pyramid, they would have secured a far greater say in the running of domestic football.

It was a wholly unsurprising attempt at a power-grab. As a source revealed, the American owner of one of England's biggest clubs still cannot get his head around the fact that his world-renowned outfit has the same amount of votes as Burnley – one.

The concept of relegation has also proven difficult for some recent arrivals to the Premier League to comprehend, along with the absence of guaranteed participation in the Champions League. Nonetheless, European clubs remain a very attractive option for American investors.

"US financiers believe that European sport is very cheap," Maguire tells Goal. "For example, there has been a rise in recent months of SPACS (Special Purpose Acquisition Companies). There is one called Red Ball, which is Billy Beane's, and he's raised about $500 million (£380m) with a view to buying 25 per cent of Liverpool.

"These special purpose companies get listed on the stock exchange in New York and people can buy and sell their shares, making it easier to raise debt so that the club can, in turn, raise funds. These SPACS are very much in vogue now because a lot of people made a lot of money this year as a result of the pandemic, and European teams are an attractive low-cost option.

"If you look at buying into an MLS franchise, we're talking about a $200m (£150m) entry free – and yet MLS doesn't make money. So, if you could buy a European club for similar money, and that club had the benefits of MLS, such as guaranteed income streams within a sealed-off league, that would be the best of both worlds as far as these investors from across the Atlantic are concerned."

Getty/Goal

However, the Super League is not just an American dream. It is just as appealing to European club executives devastated by the economic chaos caused by Covid-19.

Getty/Goal

However, the Super League is not just an American dream. It is just as appealing to European club executives devastated by the economic chaos caused by Covid-19.

Former Barcelona president Josep Maria Bartomeu sensationally announced in his resignation speech that he had committed to the competition on behalf of the Catalans, in a desperate bid to resolve the colossal financial problems caused by years of gross mismanagement. It is not a question of nationality, then, but background.

"The 'Big Six' in England happen to be owned by foreigners, but the point is not that the owners come from different countries but that they are billionaires, men who are in football to make money," Football Supporters' Association (FSA) chief executive Kevin Miles tells Goal.

"So, the Super League threat is likely to keep resurfacing because there are a few massive clubs whose owners or financiers see scope for even greater revenue generation by reconfiguring European competitions for three reasons: market the European competitions more aggressively against the domestic competitions; share their money with fewer people; and eliminate the risk of not qualifying for European competition. Basically, they don't want any intruders at the top table."

Indeed, while Leicester's title triumph in 2016 was viewed as a fairy tale by football fans across the globe, the president of one top Italian club deemed it a nightmare, horrified by the thought of having to share Champions League revenue with a team that had not made anything like the same investment in their squad.

Ironically, a 5000-1 upset does not seem fair to clubs that have the odds stacked in their favour. The continental contingent are annoyed enough as it is by the fact that their English counterparts are making so much money from the sale of TV rights.

"Make no mistake about it," Robinson says, "there is an element of jealousy of the Premier League at play here. The team that finishes 20th in the Premier League still takes home more prize money than the winner of Ligue 1, and that doesn't sit well with a lot of big European clubs.

"I think that in places like Italy, Germany, France and Spain they missed the boat in the mid-90s in terms of becoming the most valuable league in Europe with respect to TV rights, and they've been trying to catch up ever since.

"So, now they want more high-value games against the clubs that draw the biggest TV audiences, as a way to close the gap to the Premier League, and keep their own clubs running at the financial level they need to stay competitive in Europe."

It seems fitting, then, that the latest reports revealed the new closed-off competition would most likely be called the 'European Premier League'. Is it really feasible, though? There would be a plethora of bureaucratic issues – even with the support of domestic leagues and UEFA, who remains dead against the idea.

Getty/Goal

Getty/GoalIn a statement given to Goal, Europe's governing body said, "The UEFA President, Aleksander Ceferin, has made it clear on many occasions that UEFA strongly opposes a Super League.

"The principles of solidarity, of promotion, relegation and open leagues are non-negotiable. It is what makes European football work and the Champions League the best sports competition in the world.

"UEFA and the clubs are committed to building on such strength, not to destroying it to create a Super League of 10, 12, even 24 clubs, which would inevitably become boring."

And that is undeniably a risk. As Maguire points out, "What happens in February when it's Arsenal against Atletico in the Super League and neither have a chance of making the knockout phase?" That's not an attractive proposition for anyone, arguably not even both sides’ fans.

Maguire, though, says that supporters have now become "nearly irrelevant" in the eyes of the game's major powerbrokers: "They are there to be monetised, patronised and convert a stadium, which is a static environment, into a living, breathing creature for the purposes of good television."

But what would happen if viewers start switching off? If the Super League is all about money, and the majority of the money comes from TV deals, surely the elimination of risk would result in low ratings?

"It is a potential issue, " Maguire acknowledges, "at least, domestically, but, for example, Manchester United's fans aren't solely based in Manchester, nor Real Madrid's in Madrid.

"That isn't a dig at their overseas followers, more a sign of their global popularity, so even if local fans lose interest, they'll still have millions left across the world, in Nigeria, China, Thailand and so on, and they just want to see their team winning and signing superstars."

Interestingly, though, one of Europe's 'Big Five' leagues recently ran an as-yet unpublished survey in Thailand that asked, among other things, whether they would like a league game between two of its great rivals to be staged in Bangkok – and the majority of those polled were against the idea because they felt the fixture would lose its unique atmosphere.

The potential dissipation of parochial passion is one of the main reasons why even former Madrid president Ramon Calderon is warning against undermining domestic leagues.

"In 2007, when I joined UEFA as vice-president of the Club Commission, we already had discussions to create a Super League but the economic and planning conditions were never clear," he reveals to Goal.

"I think it would be dangerous for major teams to turn their backs on national competitions because the leagues would be greatly weakened and it would affect fans in many cities, who would lose the opportunity to see their teams take on the best teams.

"I suppose that Real Madrid will ultimately opt for the best solution for their interests but it would seem like a mistake to leave La Liga. This Super League project could also affect grassroots football by greatly weakening small teams economically, thus preventing them from investing in academies and the development of young players."

Liga president Javier Tebas certainly believes that Super League supporters such as Perez and Bartomeu have grossly misread the situation, arguing that the very project they believe would rescue football, could actually kill it.

"Bartomeu's comments were a way of diverting attention away from his worst and final day as Barca president," he tells Goal. "Perez is a great construction entrepreneur and a great manager of Real Madrid as a club, but he does not understand what the Super League would do. He is misreading the negative effects that it would have on his club, which could lead to its ruin.

"The Super League is not the way to generate more revenue. It would ruin the national leagues, which have sustained and continue to sustain the top clubs, and anyone who thinks that the Super League is compatible with domestic competitions – be it Florentino Perez or whoever – is just wrong."

Getty/Goal

Getty/GoalThe mere fact that we are now debating the potential perils of a Super League is a reason for optimism, according to FSA chief executive Miles.

"The negative effects are now being subjected to a lot more scrutiny," he says. "With the Super League talk and ‘Project Restart’, elite clubs have actually generated an increased appetite for the independent regulation of football.

"I think that's more likely now than ever before because people are now thinking that football can't be trusted to look after itself; that it’s in real danger of eating itself.

"The UK government had already made a manifesto commitment to a fan-led review of the governance of football, which we expect to start in the New Year, and that will now have a broader remit because of the issues thrown up by ‘Project Restart’.

"So, the train is already in motion. In their efforts to take complete control of football, the game's elite will not only have to take on other clubs and leagues, they may also have to tackle governments and their own fans, which is a much tougher task."

Of course, football's major organisations will still seek more power – not less. And there is already a new battle brewing between UEFA and FIFA for control of the international club game.

An expanded and more regular Club World Cup is one of FIFA president Gianni Infantino's primary targets, while it has not escaped anyone's attention that the latest Super League reports claimed that FIFA had given its backing to a $6 billion (£4.8bn) package being put together by Wall Street bank JP Morgan.

Tebas, though, doubts whether Infantino would really be willing to move in on UEFA’s turf for the sake of a project that he deems doomed to fail.

"They talk about CVC Capital Partners, they talk about JP Morgan, they talk about many things but the reality is that with $6bn, you don't even have enough money to sustain this project for the first year," the Liga chief claims.

"There is also no financial institution out there that would be willing to put in the money needed to sustain this Super League for three-to-four years because they would be financing a war. A war with FIFA or UEFA or the domestic leagues or clubs or the fans. It would be impossible to get a new competition going without the agreement of every major group in football. It would create a tremendous ruckus.

"The Super League would only succeed in taking on football's authorities, its fans and going bankrupt."

However, top European executives are monitoring the situation with interest, and Maguire believes that loyalty will not be a factor when it comes to deciding which body to support if rival bids are tabled.

“The big clubs will just go with whoever offers them the most money,” he says. “FIFA loses money three years out of every four. They only make money in World Cup years. The Champions League is football's most lucrative club competition, so if FIFA could get control of something like that, they would start making money on an annual basis.

"UEFA are aware of the threat of a Super League and we’ve seen them give way to the larger clubs on the 10-year coefficient, in terms of the distribution of Champions League money, so what they're essentially saying is, 'We acknowledge that you are the biggest draws and if, on a given year, you have a terrible season, don't worry, we've got your backs.'

"FIFA will be prepared to offer guarantees of a similar nature, so there's a big decision coming for top clubs."

Getty/Goal

Getty/GoalClearly, change is coming, too. It is just a question of how much – and who will benefit?

Juventus president Agnelli has long pushed for reform and has repeatedly pointed out that there was initial resistance to the Champions League “and now everyone loves it”, which is not strictly true, given its contribution to the growing disparity of wealth in European football.

Regardless, the FSA has been at pains to stress that it is against a Super League – not reformation. It has little interest in maintaining the status quo, not when football's financial model is so badly skewed, as the pandemic has so forcefully underlined. It, like the Premier League, UEFA, the ECA and so many other groups, wants change too – just for different reasons.

As it stands, the most likely outcome is the expansion of the group stage of the Champions League and significant alterations to the qualification process.

"The top clubs don't necessarily want a closed shop; a lot of them are too smart for that," Robinson says. "They know that not playing in a domestic league would hurt their product. They're not stupid. Even if you've suddenly got 20 of the biggest clubs in Europe playing in a Super League, somebody still has to finish last.

"So, what they would all like to do is maximise the number of high-value games they play in Europe against the other big teams, meaning a 10-game group stage is much more likely than a full breakaway. I think you're also going to end up with a route back into the Champions League via the Champions League, based on past results.

"You're going to have protected seeding, a safety net, essentially, because they're all performing this high-wire balancing act every year as their business model depends on qualification.

"So, if you think of all of this Super League and Champions League reform talk within that fragile financial framework, all of the panicked reactions and radical ideas being put forward make perfect sense."

Indeed, the threat of a Super League isn't going to "f*ck off" any time soon – not with so much money at stake. For better or for worse, it's going to play a key role in the battle for control of club football.

And depending on the outcome, we could be about to witness the rebirth of 'the beautiful game' – or its death.