Atalanta CEO Luca Percassi told Sky Sport Italia earlier this year, "Football is meritocracy." Sadly, that is not a view shared by the game's most powerful men.

European Club Association chairperson Andrea Agnelli even publicly asked whether Atalanta really deserved to participate in last year's Champions League – despite the fact that La Dea had earned their spot via a third-placed finish in Serie A.

Amusingly, Atalanta went further in Europe's premier club competition than Agnelli's Juventus, reaching the quarter-finals in their tournament debut.

We should enjoy such fairy tales while we can, though. The European Super League is edging ever closer.

Former Barcelona president Josep Maria Bartomeu sensationally revealed during his resignation speech last week that the board had approved the club's participation in a "project promoted by the big clubs in Europe".

Bartomeu claimed that the Super League would "change the club's revenue prospects for the coming years".

It was a pathetic act of desperation, a last-gasp attempt to undo the financial damage caused by his years of gross mismanagement.

But this is where we, as football fans, are at now. The economic crisis caused by the coronavirus pandemic has not just exposed the game's flawed business model; it has terrified its biggest clubs.

Agnelli and his peers have long dreamed of a European Super League to expand their businesses; now the likes of Barcelona believe they need it to survive.

They are seeking financial security, a closed-off competition that guarantees a certain amount of games – and a certain amount of money.

Football, like any sport, is not supposed to offer guarantees, of course; its unpredictability is what makes it so appealing to fans. Yet the uncertainty unsettles Agnelli & Co.

Even though the balance of power in modern football has been shifted dramatically in favour of the biggest clubs, an element of surprise remains. Atalanta are proof of that.

Their emergence as a major force in Italian football shows what is possible for well-run clubs. They have illustrated the benefits of a fruitful academy and a sensible transfer strategy.

“We select players for roles that the coach indicates, but also have to take into account that we cannot go beyond a certain figure," Atalanta president Antonio Percassi – Luca's father – told Sky last season. "Keeping the books balanced is fundamental for us."

That is not easy in an era of spiralling wage bills, but it helps that Atalanta have arguably become the masters of the transfer market.

Getty/Goal

Getty/Goal

Last January, they agreed a deal with Juventus for Dejan Kulusevski – whom they signed from Brommapojkarna for €100,000 (£90,000/$116,000) – that could end up being worth €44m (£40m/$51m) to the Bergamo-based side.

This January, youth-team star Amad Diallo will join Manchester United for an initial fee of €21 million (£19m/$25m) that could rise to €41m (£37m/$48m).

Consequently, Atalanta now stand to pocket €85m (£76m/$99m) from two players that had made just six appearances for their senior squad.

For many ambitious clubs, there would be an obvious temptation to invest all of that money in new signings for the first team. However, Antonio and Luca Percassi need no convincing of the importance of the youth sector to a club's success – they both began their respective playing careers at Atalanta's academy.

Former defender Antonio was forced to quit the game at the age of 24 because of a serious injury, but he went on to make a small fortune working with Benetton and investing in the make-up industry. When he became Atalanta president in 1990, he made one decision that would have lasting effects.

In 1991, Percassi hired Como's Mino Favini to overhaul Atalanta's youth sector. Just two years later, the club claimed its first ever Primavera title.

"I take those who have an aptitude for football, rather than those who are big and strong," Favini later told the Gazzetta dello Sport of his recruitment strategy. "But you also need heart and soul. Physicality, athleticism and tactics come later, because they can be developed.

"Then, up until the age of 14, the boys work almost always with the ball. The definition of their role comes only with the Allievi (Under-17s), and is also based on the boy’s intellectual capabilities."

Getty/Goal

Getty/Goal

As if to underline the point, at the end of every season, Atalanta's youth sector awards a prize ('Premio Brembo') to the most deserving boy or girl, taking their performances, behaviour and scholastic achievement into consideration.

Favini – who sadly passed away last year after three decades working at Atalanta – was more interested in players who were strong mentally, rather than physically. He wanted to produce determined but selfless characters who understood the importance of playing for the team.

"We don't create phenomena," he admitted. "But we do create good players." And lots of them.

In the past four years alone, Franck Kessie (€28m), Andrea Conti (€24m), Roberto Gagliardini (€22m), Mattia Caldara (€15m, but now back at the club on loan from AC Milan), Alessandro Bastoni (€31m) and Musa Barrow (€13m) have all come through the Atalanta youth-team ranks and been sold for a combined profit of €133m (£120m/$155m), which contributed to the club being able to take ownership of its home ground (Gewiss Stadium) in 2017.

However, there has been a noticeable shift in Atalanta's strategy of late.

Firstly, in terms of recruitment, the club is now casting its net far wider since the Favini-backed arrivals of sporting director Giovanni Sartori and academy chief Maurizio Costanzi from Chievo six years ago. There were 19 Italians in Atalanta's 30-strong squad for the 2014-15 season. In January of last year, they fielded a team in the Coppa Italia containing 11 foreigners.

Secondly, there are no longer as many youth-team products in the first team; as the cases of Barrow, Kulusevski and Diallo underline, potential stars are now often sold before they become first-team regulars.

What Atalanta have instead been doing in recent years is unearthing rough diamonds that others have overlooked, or kickstarting the careers of players who have struggled at supposedly bigger clubs.

Getty/Goal

Getty/Goal

Papu Gomez, Josip Ilicic and Duvan Zapata are the most noteworthy success stories, given they now form one of the most exciting attacking trios in European football.

However, it is worth noting that not one of Hans Hateboer (Germany), Martin de Roon (Netherlands) or Remo Freuler (Switzerland) was playing international football before they arrived in Bergamo.

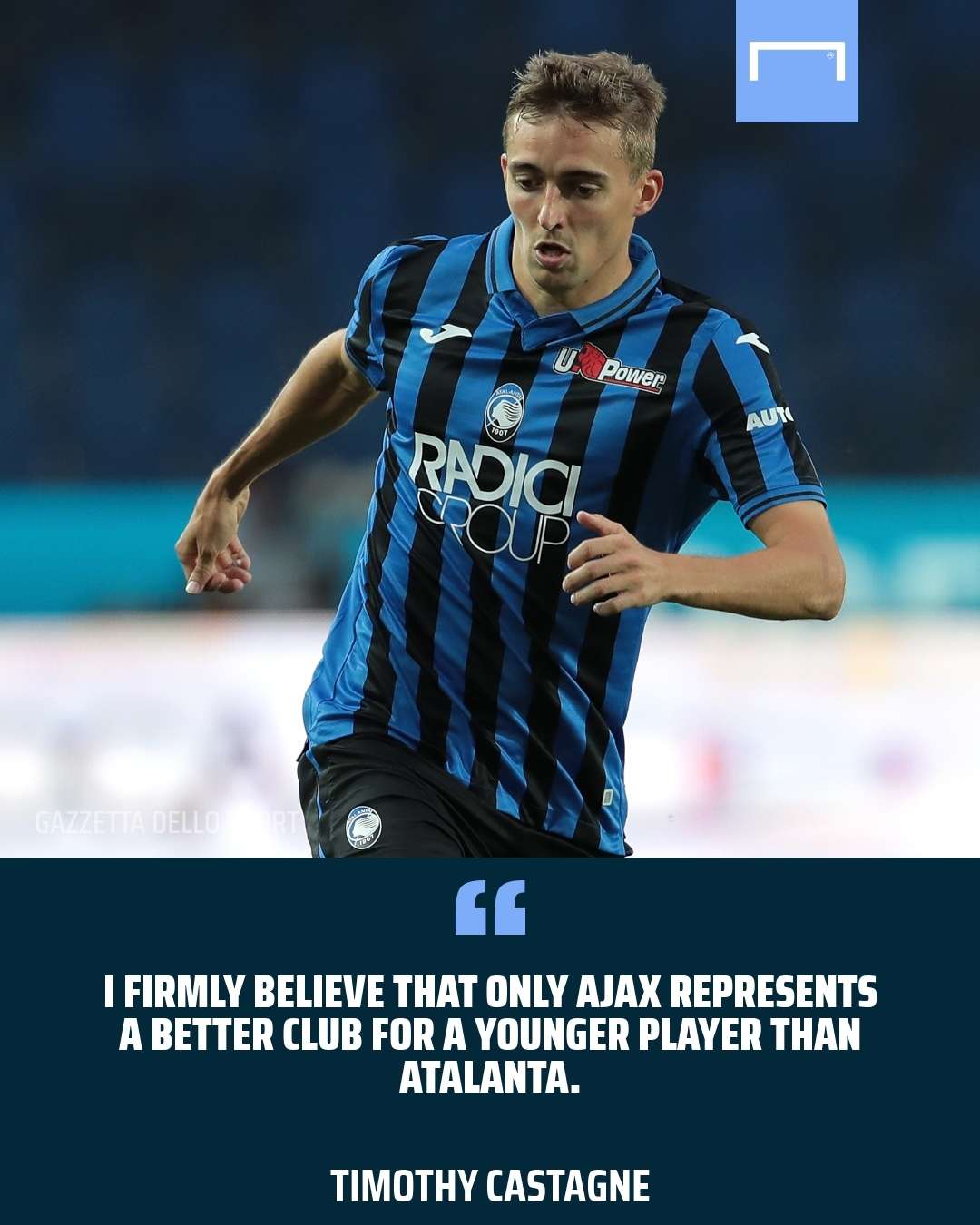

The same goes for Timothy Castagne, who was signed from Genk in 2017 for €6.5m (£5m) and sold to Leicester City during the summer for €24m (£21.5m).

"I firmly believe that only Ajax represents a better club for a younger player than Atalanta," the 24-year-old Belgian told Gazzetta.

Castagne's case is particularly significant, too, in that Atalanta could afford to let him leave. As Antonio Percassi has pointed out, the club is no longer compelled to sell its best players every summer.

The team's success – Champions League qualification two years in a row – has put the club in a far stronger financial position. It is not first-team stars such as Kessie and Gagliardini who are now exiting, but squad players and youth-team prospects.

Atalanta B.C.

Atalanta B.C.

Atalanta's wage bill remains relatively small – only the 11th-biggest in Serie A, according to Gazzetta – but it did increase marginally (€6m) during the summer, which is noteworthy given the current economic crisis. In addition, the youth sector continues to go from strength to strength.

Atalanta's Primavera have won the last two Italian titles, while last November saw the official inauguration of the Mino Favini Academy – a state-of-the-art facility dedicated entirely to the youth sector, which consists of 17 teams and 367 registered boys and girls.

Significant expansion work has also taken place at the club's training centre at Zingonia, the Centro Bortolotti, where the youth teams train on pitches alongside the senior squad, which only serves to highlight the tight-knit nature of a club where everyone is pulling in the same direction.

“Our progress has not been a fluke," Luca Percassi told Sky. "It has been a constant growth and we intend to keep that process going."

In an ideal world, of course, Atalanta would have no need to cash in on exciting young talents like Diallo and Kulusevski, but the football world is far from ideal.

What the Bergamaschi are doing, though, is growing one step at a time by developing players to sustain the entire operation through timely transfers.

Getty/Goal

In that context, it is easy to understand why Luca Percassi claimed that the Diallo deal was one that Atalanta simply “couldn't refuse”.

Getty/Goal

In that context, it is easy to understand why Luca Percassi claimed that the Diallo deal was one that Atalanta simply “couldn't refuse”.

"This kind of transfer leads to the growth of the club and enriches the work of everyone, from the general manager Umberto Marino to the staff," he explained to L’Eco di Bergamo.

"It was an indispensable deal. If Diallo is not lucky, we're protected. But if the boy becomes great, we will get recognition."

They already have that, though.

On Tuesday night, Atalanta will host Liverpool in the Champions League and the Merseysiders' manager, Jurgen Klopp, is looking forward to going up against one of the most attacking teams in Europe.

"Atalanta have a really exciting project," the German told reporters after the group-stage draw last month. "They play good football and were the revelation of last season.

"If a team is in this group, or the Champions League in general, it's because they deserve to be there."

And Atalanta definitely deserve to be there. Football, after all, is meritocracy.

Though Agnelli might disagree, of course.